#

Demystifying Final Cut Pro XMLs

Written by Philip Hodgetts & Dr Gregory Clarke from Intelligent Assistance

This article was originally written for fcp.co back in 2017.

Philip & Gregory have kindly allowed us to release it on FCP Cafe. Thank you!

#

Introduction

About ten years ago I wrote an article for KenStone.net called What is XML, and what does it mean for Final Cut Studio users. In that ten years we’ve had a new version of Final Cut Pro with a whole new XML structure, and Premiere Pro CC has added import and export of Final Cut Pro classic XML.

There is a broad ecosystem of apps that depend on XML from Final Cut Pro X or Premiere Pro, many from our company, Intelligent Assistance Software.

Without the ability to round-trip XML it would be up to Apple to implement every single requested feature. We know full well that niche workflows — the type easily supported by XML — take a lot longer to reach the top of the implementation list. Many desirable features will never make it to the main app. An open, well documented, XML interchange format allows third party developers to fill these niches and extend Final Cut Pro X without having to seek permission from anyone.

#

What is XML?

It’s likely you’ve heard the term XML and even used some of the workflow or translation apps that it enables, but still aren’t really sure what it is, and how it gets used. That’s not surprising because “XML” is an umbrella term for a way of presenting information that is:

- Human and machine readable

- Self-describing

When you first look at an XML file, it hardly seems human readable, but it is once you gain a little basic understanding. Most importantly it is readable by software, so Final Cut Pro X can import the XML that describes a Project, Event or Library. Similarly FCP classic and Premiere Pro can import Bins of clips and Projects from the appropriate XML.

That last point is important - from the appropriate XML - because there is no single “XML”. Each type of XML is unique to the application it supports because an XML file describes the data structures of that application.

It should come as no surprise, then that the XML from, or for, Final Cut Pro X is as completely different as Final Cut Pro X is from FCP classic (spoiler alert: there are no tracks in FCPX XML).

In fact, almost the first thing any XML file does is to declare what type of XML it is.

#

Figure 1

Classic FCP (and Premiere Pro CC) is xmeml:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE xmeml>

<xmeml version="4">The modern Final Cut Pro X XML is fcpxml:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE fcpxml>

<fcpxml version="1.6">Motion .motn file (which is actually XML) is ozml:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE ozxmlscene>

<ozml version="5.7">These days, the dominant user of xmeml is Premiere Pro CC. For many years now Premiere Pro has imported, and exported, a variation of xmeml. Certainly all development work on our XML translation apps since 2013 has gone to support Premiere Pro’s version of xmeml.

Premiere Pro works with a slightly modified xmeml based on the XML from FCP Classic version 6 — not the latest — that has Adobe specific tags included. Throughout this article we’ll be comparing XML from Final Cut Pro X and from Premiere Pro CC.

The second main attribute — self-describing — is an important benefit we get with XML over other formats like an EDL, or Comma Separated Variables (CSV). With these other data formats we only get the data. It’s up to the user, or software, to know what each element represents.

#

Figure 2

Here’s some data from an EDL:

001 100 V C 01:00:35:19 01:00:49:19 00:59:56:12 01:00:10:12

* CLIP NAME: 2014-05-05 14_53_37 TRIM (A)

002 100 V C 01:00:51:15 01:01:17:00 01:00:10:12 01:00:35:25

* CLIP NAME: 2014-05-05 14_53_37 TRIM (A)

003 100 V C 01:01:18:21 01:01:50:12 01:00:35:25 01:01:07:18

* CLIP NAME: 2014-05-05 14_53_37 TRIM (A)With XML each element in the file describes exactly what type of data is going to be presented, as we'll see shortly. In the next section we’ll elaborate on what an element is, and how it fits into Final Cut Pro XML.

#

What’s inside XML?

If you’ve done any HTML work for the web or other purpose, then you’ll probably notice that XML looks a little familiar. That’s not surprising because they are both Markup Languages (the ‘ML’ in both cases).

For the web we mark up text with a HyperText Markup Language (HTML), which works well for pages of text. But for editing (or motion graphics in Motion) we want to transfer an almost infinite range of different information, which is why the X is for eXtensible. HTML is limited to display options, whereas XML, because it's extensible, does not have limits to the type of data that can be marked up.

Both HTML and XML mark up using tags. HTML marks up blocks of text to tell the browser how to display it. XML marks up blocks of data with tags that tell us what type of information or data is stored.

These markup tags tell us what type of data is stored between the tag ‘open’ and the ‘close’. A simple HTML example would be like this:

<p> at the <b>beginning</b> of a paragraph </p>There are two sets of tags in this example: the pair of 'p' tags tell the browser to display all the text between the opening <p> and closing </p> tags as a paragraph, and the pair of <b> </b> tags tell the browser to display the word "beginning" in bold.

Likewise in an XML file there are tags. but these tags tell the reader or computer what type of information is between the tags. Instead of paragraphs we might have <timecode> at the start of a Timecode entry, and </timecode> at the end of a Timecode entry. Like the <b> </b> tags in the paragraph above, all XML tags can nest as well. This means we can have this piece of XML code that gives keyword and marker details for a Clip (out of a FCP X XML export):

<keyword start="3600s" duration="500s" value=“Interview"/>

<marker start="4000s" duration="1s" value="Answer"/>In this example, the keyword tag is “self closing” by the simple use of / inside the last >. It also nests data within the tag as attributes. Start, duration and value are attributes for the tag keyword.

It’s a much more efficient structure, which is one of the reasons why fcpxml is so much more concise than xmeml. Expressed the old way without attributes this data would look something like:

<keyword>

<start>3600s</start>

<duration>500s</duration>

<value>Interview</value>

</keyword>

<marker>

<start>4000s</start>

<duration>1s</duration>

<value>Answer</value>

</marker>XML tags define the type of data that is between the tags. An EDL file, which also carries data about clips and edits (but a much older format) contains only data. Unless you know in advance what each item in each line in the EDL above means, you can't infer it. With XML that data would be explicitly described by being marked up with tags. (An EDL file usually describes the types of data in the first line.)

Each type of XML file customizes the tags for the appropriate data in that file. Premiere Pro and Final Cut Pro classic’s XML describes clips (and other items) within a project’s video and audio tracks. Final Cut Pro X’s XML describes clips (and others) within a project’s single primary storyline, with connected clips (and others) and secondary storylines connected to items in the primary storyline. That is why we can’t open XML out of Premiere Pro directly in Final Cut Pro X, or vice versa. They, literally, do not speak the same language.

So it’s important that we know which type of XML file we're talking about and which version. In Figure 1 you can see that we have the type of XML, and also the version number. The version number is also important. Final Cut Pro X version 10.2 can open version 1.5 of fcpxml, but it cannot open version 1.6 from 10.3. (Final Cut Pro X 10.3 allows saving as version 1.5 XML for this reason, and opens older versions of fcpxml.)

#

XML or AAF?

As well as Premiere Pro and FCP Classic, there are other applications like Media 100 and Sony Vegas — among others — that support xmeml. There is increasing support for Final Cut Pro X’s fcpxml format other than in the app itself. For example, Atomos recorders only output fcpxml, and Logic Pro X imports fcpxml. Resolve supports both versions for timelines.

The only NLE that supports no version of XML is Avid’s Media Composer. Avid helped develop the ‘open’ Advanced Authoring Format, or AAF, and uses that for it’s Project format on disc.

The primary difference between AAF and XML, beyond the fact that they’re representing different data structures, is that AAF is a binary format that is only machine readable, while XML is presented as plain text, which both machines and people can read. (Maybe you too, by the end of this article.)

Both Premiere Pro CC and Resolve will attempt to translate edited timelines between XML and AAF, and are generally successful with simple timelines, but it’s unlikely effects and transitions will be fully compatible.

#

Let’s get practical

We think it helps to have practical examples that introduce the two types of XML we’re interested in: xmeml (Premiere Pro) and fcpxml (Final Cut Pro X). As we work through the examples you’ll learn how to read the XML and learn some of its functionality.

For our example, we’ll be working on extracting a clip’s Keywords from Final Cut Pro X, and extracting a clips Markers from Premiere Pro. These examples are as similar as we could make them.

From both Final Cut Pro X and Premiere Pro you can view XML by exporting an XML file from a Final Cut Pro X Event or Library, or Premiere Pro Project. XML files can be opened in a text editor to view the content. For the best experience reading an XML file, we recommend a text editor that can do “folding” (which allows you to collapse a block of XML between start and end tags into a single line) such as TextWrangler — available for free in the Mac App Store.

#

Finding a clip’s keywords in Final Cut Pro X XML

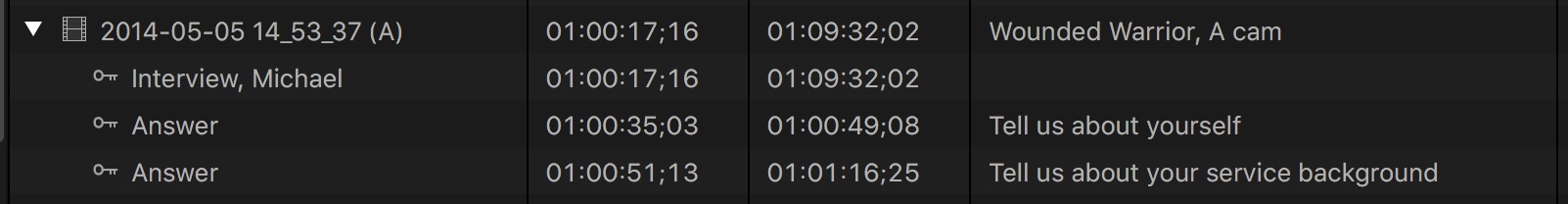

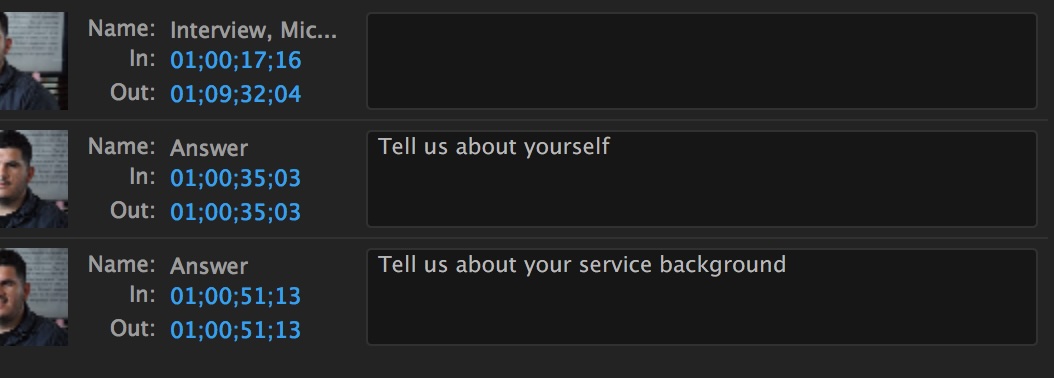

Here’s a simple example: an interview clip with a Note, and for organization there’s a couple of Keywords on the whole clip and two “Answer” keywords covering part of the interview. In the keyword’s Notes fields there’s some text outlining the question that was asked in this part of the interview. Here’s what it looks like in FCPX’s Event:

We’re going to use the exported Event .fcpxml to find some information: the file path to the media file, clip frame rate, clip note and keywords.

At the top of the .fcpxml file is a resources area which has information about media assets, formats, titles/generators/effects, and even multicam and compound clips used in the export. Here’s a trimmed version of the resources area describing this clip:

<resources>

<asset id="r1" name="2014-05-05 14_53_37 trim (A)" uid="BC4F2ECE4BDCDA28FCFE245355800DEB" src="file:///Users/greg/Footage/Wounded%20Warrior/2014-05-05%2014_53_37%20trim%20(A).mov" start="651158508/180000s" duration="49903855/90000s" hasVideo="1" format="r2" hasAudio="1" audioSources="1" audioChannels="2" audioRate="48000">

<metadata>

<md key="com.apple.proapps.mio.cameraName" value="CLOSE"/>

</metadata>

</asset>

<format id="r2" name="FFVideoFormat1080i5994" frameDuration="2002/60000s" fieldOrder="upper first" width="1920" height="1080"/>

</resources>Note: Each asset — media file — has a block of XML like this one. We’re keeping it to a single clip to make it easier to follow.

The asset element has lots of information about the media file:

- the media name is in the name attribute

- the file path is in the src attribute (Note: %20 represents a space in a way that software won’t be confused — technically it’s ‘escaped’ in the same way you would need to for an Internet URL).

- we can see there’s 2 audio channels

- with an audio rate of 48,000Hz

- it’s been given Camera Name metadata “CLOSE”.

It’s even been given a resource id number and a uid (unique identifier) — just what you’d expect from an app built on a database.

The asset has been tagged with a format attribute (with its own resource id number), and the format element with id=“r2” is defined later in the resources area. Final Cut Pro X has format definitions for all video formats: a surprisingly large number of them as it turns out.

So we know the media is 1920x1080, but what does that frameDuration number mean?

2002/60000 is a rational number describing the duration of a single frame as a fraction of a second (literally the seconds-per-frame). The frame rate (in frames-per-second) is actually the inverse of this: 60000/2002 = 29.97002997 frames per second. OK, so it’s 29.97 fps (which is NTSC 30 fps), so why bother with the rational number? Because it’s way more accurate than 30 or even 29.97! (If this was 25 fps PAL footage the frameDuration would be 100/2500s.)

Time to look at the clip and its keywords (this is 10.3’s new version 1.6 XML). This asset-clip in the Event represents the asset we've just seen because the ref=“r1” attribute points to the asset with id=“r1”:

<event name="A Single Clip" uid="188233E2-EF34-4881-A986-61CA405BAEB3">

<asset-clip name="2014-05-05 14_53_37 (A)" ref="r1" duration="399230840/720000s" start="651158508/180000s" audioRole="dialogue" format="r2" tcFormat="DF" modDate="2016-12-13 16:01:05 +1100">

<note>Wounded Warrior, A cam</note>

<keyword start="54263209/15000s" duration="33269236/60000s" value="Interview, Michael"/>

<keyword start="7270263/2000s" duration="850850/60000s" value="Answer" note="Tell us about yourself"/>

<keyword start="21908887/6000s" duration="1521520/60000s" value="Answer" note="Tell us about your service background"/>

</asset-clip>

</event>Important: The asset element gives us information about the media file: the asset-clip element gives us information about the Clip in Final Cut Pro X Events or Projects.

Note: An event would normally contain multiple clips, but we’re keeping it simple.

The asset-clip element has clip information in its attributes: ref links back to the "r1" asset and format links back to the "r2" format we’ve already seen in the resources area.

The first child element of the asset-clip element is a note and its content is the text in the Notes field.

The next 3 elements represent the 4 keywords on the clip. The value attribute is the name of the keyword. Because the keywords “Interview” and “Michael” cover the same range, they are comma-separated the same as they appear in the Event.

The start attribute is where the keyword starts in absolute time: 54263209/15000 = approximately 3.618 seconds. We can convert this to frames by multiplying by the frames per second: 54263209/15000 x 60000/2002 = 108,418 frames.

The duration attribute is how long the keyword range is: 33269236/60000 x 60000/2002 = 16,618 frames.

The two “Answer” keywords both have note attributes which is the text in the keyword’s Notes fields.

Since our goal was to “find a clip’s keywords” we now have the information we need. We have one note on the clip itself - “Wounded Warrior, A Cam” which is not part of our clip’s keywords. The clip’s keywords are:

Interview, Michael from 108,418 frames with a duration of 16,618 frames

Answer from 108,945 frames with a duration of 425 frames and the note “Tell us about Yourself”

Answer from 109,435 with a duration of 760 frames and the note “Tell us about your service background”

Along the way we’ve learnt about fcpxml Resource information; how to find Keywords and how to calculate frames from Final Cut Pro X’s rational seconds.

#

Finding a clip’s markers in Premiere Pro XML

Let’s look at the same clip in Premiere Pro. We’re going to use the exported .xml to find similar information: the file path to the media file, clip frame rate, clip Log Note and Markers:

Information about a media file is in a file element which is a child of a clipitem element:

<file id="file-1">

<name>2014-05-05 14_53_37 trim (A).mov</name>

<pathurl>file://localhost///Users/greg/Footage/Wounded%20Warrior/2014-05-05%2014_53_37%20trim%20(A).mov</pathurl>

<rate>

<timebase>30</timebase>

<ntsc>TRUE</ntsc>

</rate>

<duration>16618</duration>

<timecode>

<rate>

<timebase>30</timebase>

<ntsc>TRUE</ntsc>

</rate>

<string>01;00;17;16</string>

<frame>108418</frame>

<displayformat>DF</displayformat>

</timecode>

<media>

<video>

<samplecharacteristics>

<rate>

<timebase>30</timebase>

<ntsc>TRUE</ntsc>

</rate>

<width>1920</width>

<height>1080</height>

<anamorphic>FALSE</anamorphic>

<pixelaspectratio>square</pixelaspectratio>

<fielddominance>upper</fielddominance>

</samplecharacteristics>

</video>

<audio>

<samplecharacteristics>

<depth>16</depth>

<samplerate>48000</samplerate>

</samplecharacteristics>

<channelcount>1</channelcount>

<layout>stereo</layout>

<audiochannel>

<sourcechannel>1</sourcechannel>

<channellabel>left</channellabel>

</audiochannel>

</audio>

<audio>

<samplecharacteristics>

<depth>16</depth>

<samplerate>48000</samplerate>

</samplecharacteristics>

<channelcount>1</channelcount>

<layout>stereo</layout>

<audiochannel>

<sourcechannel>2</sourcechannel>

<channellabel>right</channellabel>

</audiochannel>

</audio>

</media>

</file>Wow, that’s a lot of XML and a lot of repetition, but it’s the same information that’s in the asset and format elements in the .fcpxml file. The main difference is that the numbers represent frame counts rather than rational seconds, which makes the math a lot easier. We’d need the frame rate though to work out the duration in seconds.

The file path to the media is the content of the pathurl tag, and the frame rate is described in the rate element: timebase at 30 frames per second when ntsc is TRUE means 29.97 fps — or more accurately 30,000/1,001 or 60,000/2,002. (If this was 25 fps PAL footage the timebase would be 25 and ntsc would be FALSE.)

The first frame of the media file is 108,418 because this file has timecode and does not start at zero. We’ve also got information about the number of audio channels and the sample rate of the audio.

To save space, Premiere Pro exports this full file listing only once. Any other time it appears in the XML is a reference back to the full file listing using the unique id attribute, like this:

<file id="file-1"/>To get to the Log Note and Markers we have to skip over descriptions of the audio tracks until we get to this at the bottom of the clip:

<marker>

<name>Interview, Michael</name>

<comment></comment>

<in>0</in>

<out>16618</out>

</marker>

<marker>

<name>Answer</name>

<comment>Tell us about yourself</comment>

<in>527</in>

<out>-1</out>

</marker>

<marker>

<name>Answer</name>

<comment>Tell us about your service background</comment>

<in>1017</in>

<out>-1</out>

</marker>

<logginginfo>

<lognote>Wounded Warrior, A cam</lognote>

</logginginfo>The first marker has the name “Interview, Michael” and has in and out elements. These numbers represent the relative number of frames from the beginning of the clip, so the first marker starts at the beginning and has a duration of 16,618 - 0 = 16,618 frames which is the end of the clip (yes, markers can have a duration). The first frame of the clip is 108,418, so that’s the frame number where the marker starts.

The other two markers have an out of -1 which means they only have a single frame at the in point, and the markers are 527 and 1,017 frames respectively from the start of the clip. Markers can optionally have comment text in the comment element.(If this was XML from Final Cut Pro 7 the markers would also have red/green/blue/alpha elements describing the color of the marker, but PPro actually uses FCP6 XML which does not support colored markers.)

The Log Note is in the content of the logginginfo element’s lognote child.

We set out to find “the file path to the media file, clip frame rate, clip Log Note and Markers”

The clip frame rate comes from a combination of the timebase and ntsc elements. Combined they tell us 30 frames per second but compliant with NTSC standards. We know it as 29.97 fps.

As we saw just before the conclusion the clip log note comes from the logging info element’s lognote child element, and is Wounded Warrior, A cam.

The clip’s Markers are:

- Interview, Michael from 108,418 frames with a duration of 16,618 frames

- Answer from frame 108,945 with no duration and the note “Tell us about Yourself”

- Answer from frame 109,435 with no duration of and the note “Tell us about your service background”

#

Summary

While XML can be strange at first, with a little patience it slowly reveals itself to be the treasure trove of information that it is. We hope this short introduction has been useful and whet your appetite to learn more.